Oct 8, 2024

Ah, the internet. Creator of and destroyer of… the internet.

“Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.” -Cory Doctorow

That’s the story of Enshitification, at least according to veteran internet commentator and author Cory Doctorow, who enumerated a thesis on “The Enshitification of the Internet” in late 2022. For fans of critical theory, its outlines will be familiar: as in all cycles, technological, social, economic, and human, the Internet has arrived at an inflection point wherein the Internet as a business now drives the goings on of the Internet as a place where people live, work, and communicate. And that business is, increasingly, antimonious with the ideals that these very same companies espoused decades ago.

"Five Websites each consisting of screenshots of the other four"

The once open internet protocol that saw the creation of hundreds, then thousands, and finally millions of unique sites and businesses, is now largely a forgotten relic of a time gone by. The weird and unexpected discoveries that early web denizens made and shared via email and on small, privately hosted message boards are mostly gone, their core software no longer supported. The protocols and software upon which that internet was built, such as Adobe's Flash player, have been discontinued, and in many cases, the websites themselves have ceased to be. In their place, a handful of megasites, ad-supported, with content moderation teams and complex, opaque algorithms governing the visibility of web content have consumed much of the web.

The Oligopoly of Mediocrity

The effects of a distributed open protocol being subsumed into an oligopoly, which Doctorow acidly calls “five websites, each consisting of screenshots of text from the other four,” has been a ratcheting reduction in both the quality and the variety of speech online.

Much of what is left of the open web is a patchwork of pay-to-use sites that pretend to offer free software services, but in fact hoover up customer data for large corporate owners, or point customers toward expensive monthly subscriptions to services they don't need. While Doctorow’s views of "enshitification" are concerned with the concept of free and open speech, it is not expressly a “freeze peach” screed deriding large social media platforms that refuse to magnify the already outsized reach of culture war reactionaries.

It's not just about speech either. It's about a serious lack of transformative innovation of the web as an open platform for knowledge and wealth creation. Most of the data of the web is now proprietary. Most of the economic opportunity is now driven by a small number of hyper-scaling firms with most of the access to capital. That is the reality of the web in 2024, and it's what we're talking about today.

The role of venture capital is essential in the tech ecosystem. Without it small firms have little opportunity to test new and innovative ideas. But year after year, the bets of venture capital investors in Silicon Valley have gotten larger and more concentrated. That is not healthy or conducive to a vibrant and free internet economy.

Nor does his thesis concern only social media apps or companies. The theory drives at something deeper and more rotten than a culture of hot-takes and memes.

Instead, Doctorow points to a tendency among all big tech platforms to grow large first by offering a loss-making service with a high value for a large audience, and once that audience is locked in and dependent on that platform, gradually reversing the flow of value, so that users pay for more than they receive. That “payment” can be in the form of money or, in the world of big data, personal information.

Enshitification Theory

The above is a formula that has seen a number of hyperscalers make a fortune on the internet. But is this cycle actually killing off true innovation?

Today, Marketplace sellers are handing 45%+ of the sale price to Amazon in junk fees. The company's $31b "advertising" program is really a payola scheme that pits sellers against each other, forcing them to bid on the chance to be at the top of your search. Searching Amazon doesn't produce a list of the products that most closely match your search, it brings up a list of products whose sellers have paid the most to be at the top of that search. Those fees are built into the cost you pay for the product, and Amazon's "Most Favored Nation" requirement for sellers means that they can't sell more cheaply elsewhere, so Amazon has driven prices at every retailer. - Cory Doctorow

Doctorow’s essay lists many examples, but once you’ve got a general idea, almost any old platform will do: Amazon, Google, Meta, Netflix, Twitter, or Uber. All these companies have a lifecycle in common: they begin with an offer that’s not only good but often too good. All the Hollywood movies you can watch for a few bucks a month? The entire internet mapped out for you in real time, for free? A car that can pick you up anywhere, anytime, and is cheaper than a taxi? What's suspicious about any of these offers?

Well, as they used to say: who bells the cat? Or put in a slightly less macabre fashion: who ultimately pays for this amazing, cheap, and accessible service where you get more than you pay for? Why of course, the sellers who use Amazon, the websites that Google indexes, and the drivers who drive for Uber. Once venture capital has been expended, investors expect value to be returned to them. It can only come from one of two places: either you pay for it, or an army of low-wage workers will.

Sometimes, the promise is built upon an unsustainable lack of legal regulation, as in the case of Uber or Airbnb. Sometimes it's built upon the exploitation of a class of workers, as in Uber and Netflix, which failed to pay screen actors a fair share of royalties from the beginning, simply because Netflix was "not television." Never mind that to the viewer, Netflix was even more valuable than television had ever been. Once they were used to paying an unsustainable price for such amazing convenience, viewers would be ready to accept that the working actors and crew members involved would never get their share of the royalties. Spotify did exactly the same thing, and that model has been copied repeatedly.

These unsustainable practices inevitably lead to compromises, both in the quality of the product and the conditions of the workers who provide the value behind the service. Eventually, too, these unsustainable practices lead to higher prices, to make them finally sustainable, and indeed profitable. In this way, we are all being made to pay for the unrealistic vision these tech giants once sold us. Today, Uber in the United States is often taking more than half of what you pay for a ride. An Airbnb is no longer cheaper than a hotel. And your streaming subscription packages are costing you much more than you were probably paying for cable years ago. Yet behind this, workers continue to be exploited, regulations continue to be skirted, and quality continues to slide. A new class of wealthy investors have gotten richer than anyone ever has been before, and you've paid for that.

This is enshittification: surpluses are first directed to users; then, once they're locked in, surpluses go to suppliers; then once they're locked in, the surplus is handed to shareholders and the platform becomes a useless pile of shit. From mobile app stores to Steam, from Facebook to Twitter, this is the enshittification lifecycle. - Cory Doctorow

The problem extends beyond products and online services as well. As blogger Tara McMullin points out in a great blog post on the topic. It applies to content, and indeed to the very idea of people in an online space. As spaces become more established, the necessity and demand for self-promotion also increase. As audiences become easier to reach, the quality of what reaches them is bound to drop.

You can't have a big, accessible platform that reaches the whole world without it veritably filling with crap. It just can't happen. Eventually it will enshittify. And it will do so because ultimately that is the thing that investors are promised: that their needs (for profits) will be met.

Unsustainable Promises: The Enshitification Cycle

Working for the platform can be like working for a boss who takes money out of every paycheck for all the rules you broke, but who won't tell you what those rules are because if he told you that, then you'd figure out how to break those rules without him noticing and docking your pay. Content moderation is the only domain where security through obscurity is considered a best practice. - Cory Doctorow

It was not typical for an investor to expect a 10,000% percent return on an investment before the age of online platforms.

Back then investors who wanted to get into the software or entertainment business invested money, it was for the chance of relatively slow and steady returns. Enough perhaps to make investors a profit, but not ever enough to create fortunes the like of which the world has never seen.

Those returns come at a cost, and it is the users, and frequently the small business owners and sole traders, who always pay. As prices on Uber and Airbnb or Amazon continue to rise, the platform is making the lion’s share of the difference. When screen actors win more rights, the quality and volume of content on platforms like Netflix will fall. But you can be sure that Netflix itself will remain very profitable, or find new ways of bilking actors, writers, or production staff out of a fair paycheck and royalties. Prices will continue to rise. Ads will continue to increase.

If you have the time, watch this wonderfully weird but ultimately infuriating breakdown of how Spotify cheats artists out of the value of their music, while being owned and run for the benefit of the corporate music industry. All to serve an overblown vision of the "democratization of music."

These are all companies that talked about the future as a place where the internet had "democratized" everything form music production to journalism. And some democratizing has taken place. But has the fundamental model of how businesses made money changed? No.

Big tech, perhaps more than any other industry in recent history, has made robber barons out of the same “idealistic” founders who sold us on a vision of a free, open, and bountiful internet enabled by their technologies. Today, the internet platforms we rely on practice a kind of panoptic control of our digital lives. Every word and gesture is monetized, commodified, and sold.

There is surprisingly little room, considering that the internet is unbounded in space or time, for much of anything that doesn't push the bottom line. And maybe that should be more surprising than it is. Maybe it didn't have to be.

How can we avoid contributing to this problem? One of the answers is to consider our responsibility to be a sustainable and equitable business from the beginning. That is what doFlo is endeavoring to do.

Unreal Wealth

Incentives alone are hard to argue with. Perhaps impossible. But as Doctorow puts it:

Enshittification exerts a nearly irresistible gravity on platform capitalism. - Cory Doctorow

That's what enshitification is really all about. Money. And we don't just mean the drive to earn a profit. That's been around since capitalism (and since before capitalism). We're talking about the other kind of money. The crazy kind of money.

Once an individual’s potential for making money outstrips what anyone, with any amount of imagination, could possibly envision spending in one lifetime… weird things start happening. Midnight offers to buy $54 billion companies start flying. Companies spend tens of billions more on VR technology that no one wants and everyone seems to hate.

This is not in search of turning a dollar into a mere $2. But about turning a dollar into an endless river of money. And it's being done largely at the behest of people who are already in command of oceans of money.

This reversion to rule by the fiat of a select few might seem surprising, especially since the internet was supposed to usher in a utopian world of decentralized information sharing and economic opportunity, but the same had been said before. Once, it was the automobile and the highway system that would free people from the shackles of wage slavery, and it was the telephone that was supposed to create a utopia of free access to information.

That famously didn’t happen, and for all the same reasons. The car and highway system made people more free to move, but also enslaved its users in a suburban hell of traffic snarls and pollution. The telephone became just another means of selling things, and exerting even more control over workers.

This has become so true that entire generations of people now call it "cringe" to use the telephone - the thing that the smartphone is named for - to make actual telephone calls. There were elements of the freedom these technologies had promised, but they were largely overshadowed by the economic reality they wrought. We got something, but we gave something potentially much greater.

Once the shape of a monopoly is visible, someone will realize it and seize that opportunity.

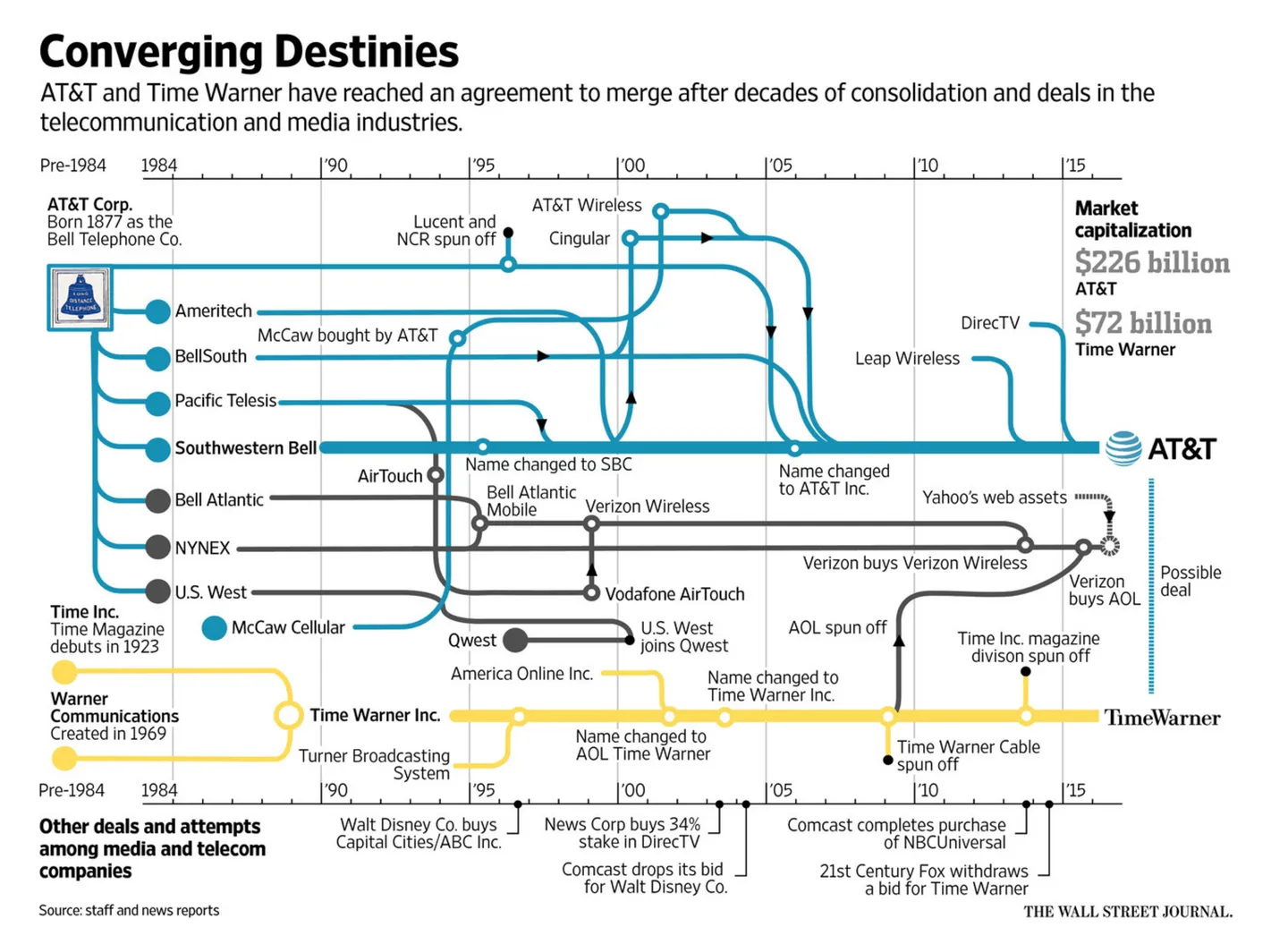

The Wall Street Journal tracks the deformation, and reformation, of the Bell Telephone monopoly.

Monopolies Re-forming

This unreal wealth has driven capital owners to seek monopoly control of the economy. The monopolies that were supposedly vanquished in the 1970s and 80s are reforming, as evidenced by the above chart of the growth of AT&T, from one of 7 spin-off companies from the regulatory breakup of Bell Telephone in 1984, into the AT&T TimeWarner we knew up until three years ago: a monopoly far larger than that of the "the phone company" in 1984. Now, a company once considered too big to exist sits astride industries it had never dreamed of dominating in the era of total monopolization of the telephone system.

[Note: since this graph was published, TimeWarner merged with HBO, At&T was spun off, and Warner then merged with Discovery Inc and became WarnerMedia in 2022 - now one of the largest media companies in the world. AT&T is now once again the largest telecommunications company in America.]

AT&T and a few others have become "the phone company," again. TimeWarner will be "the streaming company." And Meta, with the introduction of its Twitter killer Threads, "the social media company." One can hardly argue this hasn't already begun.

Populist techno-utopian visions inevitably turn to the kind of rent-seeking that has been a staple of capitalism for centuries. This shouldn't even be considered controversial. It's written into the DNA of the system. Capital simply can't help but seek monopolistic control.

Netflix displaces cable, only to become cable. Amazon kills local stores, then opens local stores. Uber displaces taxis, only to become a taxi company - but one that frequently takes a larger cut of the revenues without absorbing any of the fixed costs of owning a fleet of automobiles. Today Uber and Lyft in the United States often takes 60% of fares. The number can range even higher. Those are taxi-company fees, except taxi companies usually owned the taxis too - meaning Uber is getting their cut without taking any of the risks. Airbnb cuts out hotels with all their fees, only to become a hotelier - with all the fees.

In each case, the same abusive rentier capitalist practices of deception, bid rigging, labor intimidation, monopoly, and abuse that the technology promised to eliminate are only enabled, and intensified, by the technology.

The inescapable temptation of money being left on the table necessitates that, eventually, platforms will always enshitify: first as a means of supporting themselves, but eventually as an end in and of itself. As an industry faces headwinds and shocks, platforms find ways to shake money off the table and into their pockets. The only question seems to be how and when.

Stopping Enshitification

It seems we’re just not very good at listening when people tell us exactly what their incentives will be when they’re in charge.

If we learned anything in the 20th Century, it ought to have been that technology alone is never really enough. Yet, we can never stop believing in that next techno-utopian promise. The next open platform is going to be the one that will make people freer. That next business model is going to solve all our problems. Sure, Netflix didn’t kill cable, but the next Netflix will. Right? Amazon didn’t kill big retail… but the next Amazon will.

Good luck.

We’re in thrall to a fantasy that big business is happy to sell. But what we should be doing is looking at the people who have been selling that fantasy all along. The tech founder/CEO face-heal-turn is now almost a cliche. But that cliche may be instructive. When we pay attention, we often find that what tech founders say about their own platforms tends to be prophetic in a useful way.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin wrote in 1998, in the landmark paper that spawned one of the world’s largest tech companies: “Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine:” “Advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of consumers.” Too right.

If only people had listened to what the founders of Google, which now biases its results towards the very advertisers that they warned us about 25 years ago. If only people had listened to Elon Musk, who spent years railing against the car industry, only to adopt many of its abusive practices, as well as the owners of Twitter, only to become a cartoon villain version of those same figures a short few years later. It seems we’re just not very good at listening when people tell us exactly what their incentives will be when they’re in charge.

And how can we be surprised? Who is morally or ethically responsible enough to give up the power they accumulate through the businesses that they’ve built? And if they are that ethically rigorous, to whom can they entrust such power?

We should instead place our trust in those who are willing, from the beginning, to commit to really democratizing the economy, and passing the lions share of the value they create to the users of their own platforms.

Don't Be Shitty

What if the answers to Enshitification have existed all along? Could it be that easy?

Well, not easy. Never easy. But what if there is, in fact, an answer? Or several?

What if they're well known and popular concepts, with names that rhyme with Blegulation, Blinimum Bluniversal Blincome, and Bredistriblution?

What if the products we Enshitified were the solutions we ignored along the way? We can't pretend to know all the answers. But maybe that's a start in and of itself: to be more more open to asking: "who are we making this world better for, really?"

That requires, above all, that we acknowledge that we don't know everything. And the best we can do is to try, along the way, to not be shitty.

Lloyd Waldo is creative director at doFlo, but in a way aren't we all?